Disclaimer:

Read this article if you are not familiar with the current state of AI art.

AI art has suddenly reached a level where some feel threatened by its potential. This comes from confusion about what an artwork can be and what is required to make interesting artwork. We suddenly have a situation where everyone can generate an image that, before AI, was only available to those with the skills to create it. This creates a false sensation of accomplishment while the real labour is on the engineering side and training data (human history and human skills). The language and understanding of art have been suffering in recent times under the compromise of it being a general language affected by neoliberal capitalism, homogenous culture and lack of social innovation.

The language of art involves several aspects other than image-making itself. AI for image generation, such as Stable Diffusion and Dall-E, lacks context (historical, physicality and site specificity) and politics (incl material reality). How did we reach such a poor understanding of what art can be and what art entails?

Christian dualism’s impact on western art

Academic art was mainly read and understood simplistically through what was depicted and western art still struggles to account for the interconnectedness of artwork and images. Some questions that are relevant to a painting are; what type of canvas were these paintings painted on, where the canvases were produced, who financially funded the production of the painting, who painted it, for what reason was it painted, and what was the painting’s role in society, and in which period was it painted in. The western art tradition was also coupled with a Christian dualistic mindset, later evolving into a Christian dualistic capitalist mindset. If paintings had been understood and presented as what they were at the time (with a deeper context), they would have been uncomfortable to look at for their owners.

From: The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis

Lynn White. 1967. Science 155: 1203-1207.

One thing is so certain that it seems stupid to verbalize it: both modern technology and modern science are distinctively Occidental. Our technology has absorbed elements from all over the world, notably from China; yet everywhere today, whether in Japan or in Nigeria, successful technology is Western. Our science is the heir to all the sciences of the past, especially perhaps to the work of the great Islamic scientists of the Middle Ages, who so often outdid the ancient Greeks in skill and perspicacity: al-Razi in medicine, for example; or ibn-al-Haytham in optics; or Omar Khayyam in mathematics. Indeed, not a few works of such geniuses seem to have vanished in the original Arabic and to survive only in medieval Latin translations that helped to lay the foundations for later Western developments. Today, around the globe, all significant science is Western in style and method, whatever the pigmentation or language of the scientists.

and

The victory of Christianity over paganism was the greatest psychic revolution in the history of our culture. It has become fashionable today to say that, for better or worse, we live in the “post-Christian age.” Certainly the forms of our thinking and language have largely ceased to be Christian, but to my eye the substance often remains amazingly akin to that of the past. Our daily habits of action, for example, are dominated by an implicit faith in perpetual progress which was unknown either to Greco- Roman antiquity or to the Orient. It is rooted in, and is indefensible apart from, Judeo- Christian theology. The fact that Communists share it merely helps to show what can be demonstrated on many other grounds: that Marxism, like Islam, is a Judeo-Christian heresy. We continue today to live, as we have lived for about 1700 years, very largely in a context of Christian axioms.

and

Especially in its Western form, Christianity is the most anthropocentric religion the world has seen. As early as the 2nd century both Tertullian and Saint Irenaeus of Lyons were insisting that when God shaped Adam he was foreshadowing the image of the incarnate Christ, the Second Adam. Man shares, in great measure, God’s transcendence of nature. Christianity, in absolute contrast to ancient paganism and Asia’s religions (except, perhaps, Zorastrianism), not only established a dualism of man and nature but also insisted that it is God’s will that man exploit nature for his proper ends.

This is where the worldview often visible in Academic paintings and western art comes from. While it is less present in today’s contemporary art, it is still very present in most technological-based art because of its material and scientific connections. This worldview was/is damaging (neo-liberal capitalism) for humans, ecologically destructive and limiting in its imagination.

Francis Bacon (not the artist) has been called the father of empiricism, contributed significantly to the scientific method, and remained influential through the later stages of the scientific revolution. For Bacon, man was superior to nature. Nature was considered harsh and alienating and needed to be controlled.

From: The Novum Organum by Francis Bacon, written in Latin and published in 1620.

“Man, as the minister and interpreter of nature, does and understands as much as his observations on the order of nature, either with regard to things or the mind, permit him, and neither knows nor is capable of more.”

From: Order of man, order of nature: Francis Bacon’s idea of a

‘dominion’ over nature by E. Montuschi

Bacon ran his philosophical project on a double agenda: on one side,

the pursuit of a new science for the knowledge and control of nature and on the other side, the use of a new science for the purpose of human betterment. To make the two sides of his project combine successfully it appeared mandatory to find a way to legitimize human mastery over natural resources in such a way that scientific control and social goodness did not collide, in the respect of Christian doctrine.

From: Valerius Terminus: Of the Interpretation of Nature

by Francis Bacon

In the divine nature, both religion and philosophy hath acknowledged goodness in perfection, science or providence comprehending all things, and absolute sovereignty or kingdom. In aspiring to the throne of power, the angels transgressed and fell; in presuming to come within the oracle of knowledge, man transgressed and fell; but in pursuit towards the similitude of God’s goodness or love, which is one thing, for love is nothing else but goodness put in motion or applied, neither man or spirit ever hath transgressed, or shall transgress.

Buddhism and other worldviews

“Interbeing: If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper. Without a cloud, there will be no rain; without rain, the trees cannot grow; and without trees, we cannot make paper. The cloud is essential for the paper to exist. If the cloud is not here, the sheet of paper cannot be here either. So we can say that the cloud and the paper inter-are. “Interbeing” is a word that is not in the dictionary yet, but if we combine the prefix “inter-” with the verb “to be,” we have a new verb, inter-be. Without a cloud and the sheet of paper inter-are.

If we look into this sheet of paper even more deeply, we can see the sunshine in it. If the sunshine is not there, the forest cannot grow. In fact, nothing can grow. Even we cannot grow without sunshine. And so, we know that the sunshine is also in this sheet of paper. The paper and the sunshine inter-are. And if we continue to look, we can see the logger who cut the tree and brought it to the mill to be transformed into paper. And we see the wheat. We know the logger cannot exist without his daily bread, and therefore the wheat that became his bread is also in this sheet of paper. And the logger’s father and mother are in it too. When we look in this way, we see that without all of these things, this sheet of paper cannot exist.“

Thích Nhất Hạnh

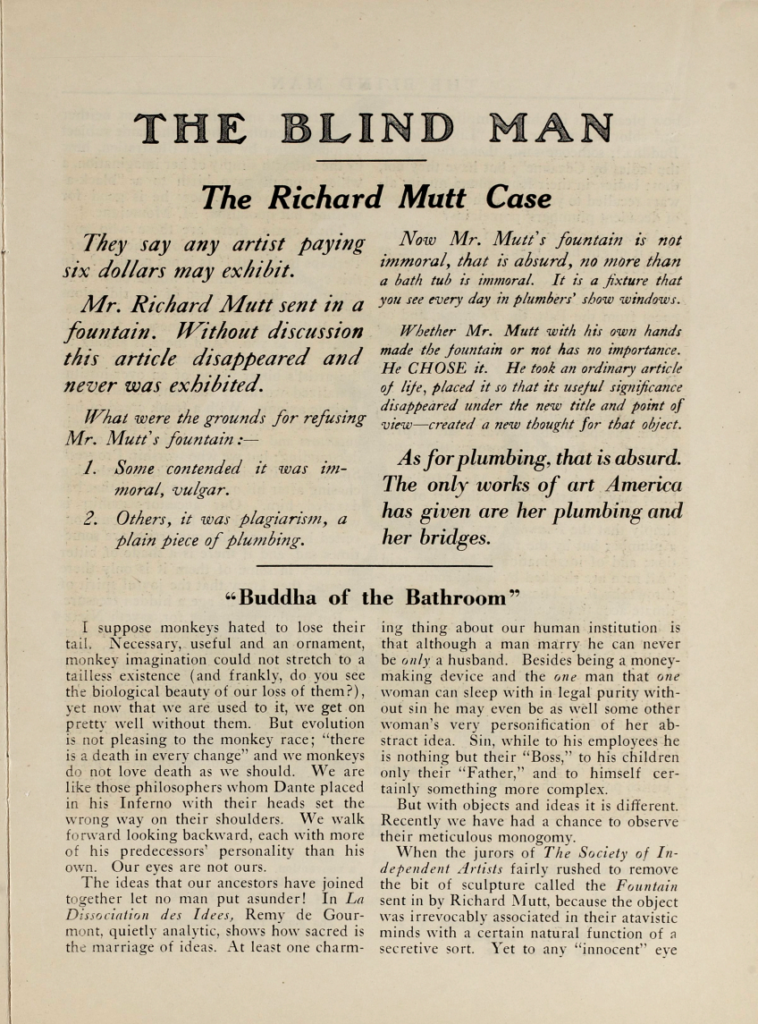

While Hạnhs understanding of objects is one of the foundations of Buddhism, it was not especially present in western art before Dada and conceptual art. In the Blind Man fanzine from May 1917, the pissoir was depicted as the Buddha of the Bathroom. It came from the newfound interest in Buddhism when D. T. Suzuki came to the US. John Cage studied with D.T. Suzuki and applied Zen to many aspects of his work. 4’33 can be considered to be a Zen Buddhist-inspired work. Freytag-Loringhoven, Duchamp and Cage were three individuals who questioned the formalism, language of art and the understanding of an artwork.

In 1969, Kosuth published his seminal essay “Art After Philosophy“, which argued that traditional art-historical discourse had reached its end.

“Modern” art and the work before seemed connected by virtue of their morphology. Another way of putting it would be that art’s “language” remained the same, but it was saying new things. The event that made conceivable the realization that it was possible to “speak another language” and still make sense in art was Marcel Duchamp’s first unassisted Ready-made. With the unassisted Ready-made, art changed its focus from the form of the language to what was being said. This means that it changed the nature of art from a question of morphology to a question of function. This change – one from “appearance” to “conception” – was the beginning of “modern” art and the beginning of conceptual art. All art (after Duchamp) is conceptual (in nature) because art only exists conceptually.

The “value” of particular artists after Duchamp can be weighed according to how much they questioned the nature of art; which is another way of saying “what they added to the conception of art” or what wasn’t there before they started. Artists question the nature of art by presenting new propositions as to art’s nature. And to do this one cannot concern oneself with the handed-down “language” of traditional art, as this activity is based on the assumption that there is only one way of framing art propositions. But the very stuff of art is indeed greatly related to “creating” new propositions.

This was a western realisation of what art was and did not account for different cultures across the world that had a different relation to art and objects pre-dating Modern, Conceptual and Traditional art. Art turned into an intellectual practice which Kosuth referred to as a process from “appearance” to “conception”. However, “conception” failed to take into account the material aspects of its concepts. After conceptual art came post-conceptual art (that accounted for the intellectual aspects of materialism) and postmodern art. None of these movements actively questioned the Christian dualist separation of man and nature (except for Sustainable art). Since conceptual art, the majority of movements still consider the intellectual aspect of an artwork and the intellectual-based materialism of artworks but yet they fail to analyze the material conditions of artwork from an ecological holistic perspective and a global political perspective. This can be considered the failure of conceptual and modern art as it did turn everything into art but failed to understand that you cannot separate man and man-made objects from nature.

Buddhism’s understanding of interconnectedness shows that understanding an object is much more than what western art discovered later on. The concept called interbeing (used by Hạnh) is built on the Buddhist principles of anatta, pratītyasamutpāda, and the Madhyamaka understanding of śūnyatā.

Madhyamaka philosophy, to say that an object dependently originated is synonymous with saying that it is “empty” (shunya). The meaning of “dependently originated” is that everything in the cosmos is a complex web of interacting causes. This is directly stated by Nāgārjuna in his Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (MMK):[215]

Whatever arises dependently, is explained as empty. Thus dependent attribution, is the middle way. Since there is nothing whatever, that is not dependently existent. For that reason, there is nothing whatsoever that is not empty. — MMK, Ch. 24.18-19 [216]

However, Buddhism thrived in Asia by exploiting nature and revering wealth, not by espousing something akin to modern environmental sensibilities, argues Johan Elverskog in his book.

From Payne on Elverskog

So, what attitude is appropriate in response to this perspective on the history of Buddhist teachings and actions in relation to the environment? Elverskog carefully avoids the temptation to turn in the direction of a “truth of Buddhism revealed” sort of thing. Nor does he follow the path of easy cynicism—“religious institutions are corrupt, so what can you expect?” Nor does he essentialize a positive interpretation of Buddhism—” that may be true, but Buddhism is really all about ending suffering for all sentient beings, and this is all just a mistaken understanding of the true teachings.” Instead, Elverskog points to the reflexive relevance of the teaching of impermanence for Buddhism per se. Buddhist teachings are always being reinterpreted and as a consequence Buddhism is itself subject to change. As Elverskog says in his closing summary:

[T]he Buddha also taught that everything changes. And thus the history of Buddhism might give us a glimmer of hope since the Dharma has itself changed. It is no longer a tradition premised on the creative destruction of the commodity frontier. Rather, if anything, Buddhists are now at the forefront of environmental awareness and action. The recent environmental history of Buddhism shows us that traditions and people—and thus the world they live in—can in fact radically change. (p. 120)

There are several other examples of different materialism from other cultures. Nuu-chah-nulth, one of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast in Canada has their own expression of how they view objects around them:

“Hishuk-ish-ts’awalk; Everything is one, and all is interconnected”

In this video, they describe their philosophy:

“We recognize that all life are precious and contains a spirit, and none are superior or inferior to another. Our life stems from the abundance from the ocean and land”

This I Am Your Sunshine and Your Shadow created by Nuu-chah-nulth artist by Joshua Prescott

The meaning is the use.

The importance of understanding an artwork with all its potential connections opens up a much better understanding of the current limitations of AI art. While modern and contemporary art and its non-western predecessors had a more open view of the complexity of an art object, AI art often lacks this complexity because of its limitations in the dataset, presentation, scale and content. AI art presents images stripped of context and often generated with the help of a prompt. Most of its viewers cannot understand its original references because of the large dataset it comes from; they mainly focus on understanding the formal aspects and its depicted content. You leave it up to the viewer to know the references in the dataset to understand its origins.

With a closer inspection, several realities are present in each AI image and AI use. Every dataset contains biases because they reflect the biases of the culture it comes from. Every culture or empire has its own biases to justify its existence. The biases in the global north are connected to imagination, financial and material reality, cultural hegemony, semantic biases etc.

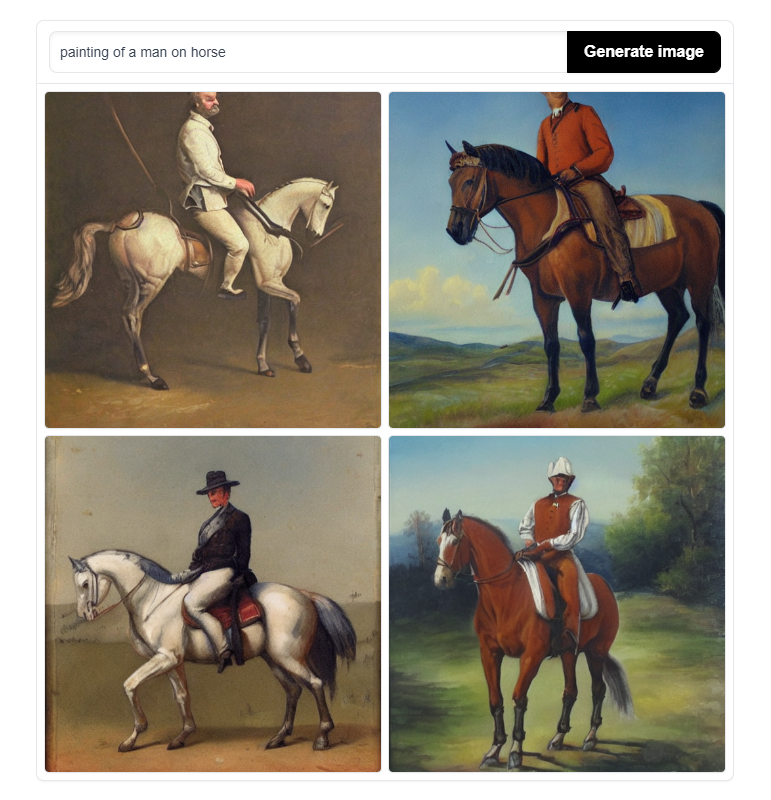

Lack of imagination

The homogeneity of western culture is what is reinforced in the datasets of the current AI art. When it is reinforced in the datasets, it will also be reinforced in its output. The limited language of art (or limited language in general), limited imagination from affluent western artists and limited access for the global south and marginalized people to use and develop the AI tools further create new biases. There will be fewer images from countries in the global south, especially from financially poor areas, unless it’s accounted for and balanced out (balancing this would most likely be a western-based balancing which again would create another bias).

If a better and more diverse understanding of an object had been present in the western world, the lack of imagination in image making would have been less severe (it’s also limited by other factors such as biology and physics). Most images generated with AI and its datasets will be inside the norm of humans from the global north and their use cases. This will reinforce the validity of those images in the dataset and create a more substantial western bias based on their imagination and language of art.

An example of a bias exists in all the untranslateable words and sayings that existed before colonizers and wars destroyed cultures and their languages.

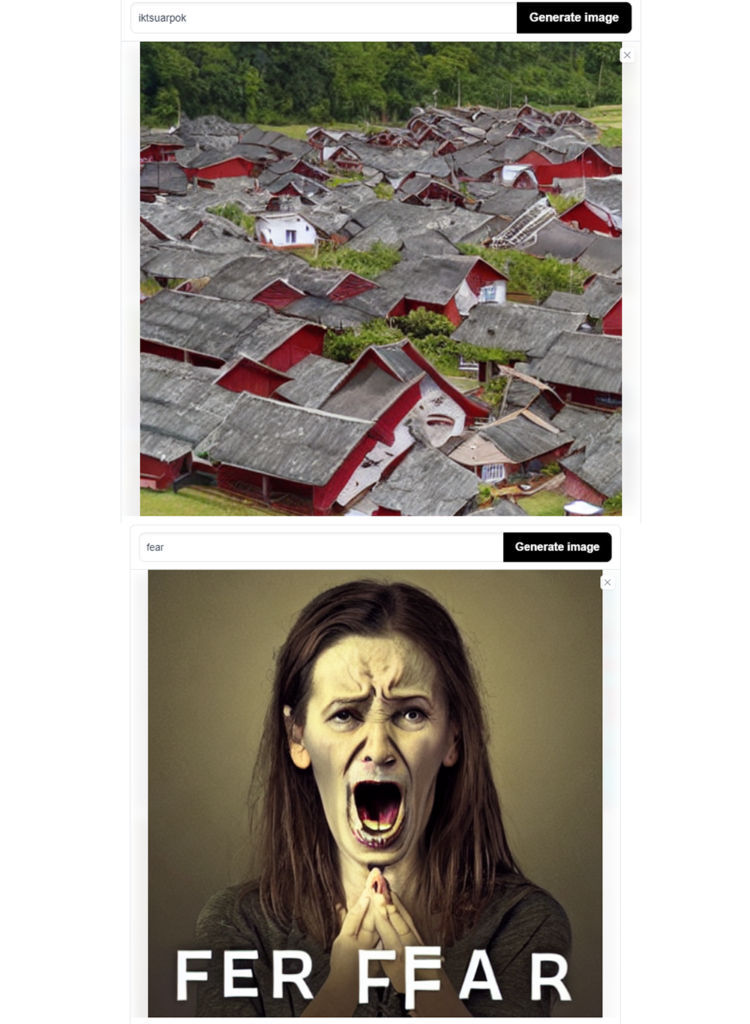

Untranslatable words and phrases in our current world are also not especially present in the dataset, and since this is mainly based on English it does not represent other cultures well unless you can translate the words. The example above is from a prompt-based stable diffusion model.

Represented by the words “fear” and the Inuit word “iktsuarpok” (The feeling of anticipation while waiting for someone to arrive, often leading to intermittently going outside to check for them.). The noticeable difference in clarity and content shows the bias toward western-based concepts. I’m sure this can be explored further (it’s not the best example, I admit) but it’s quite evident that prompt-based models will have semantic issues. This is most likely because of the number of images labelled under “fear” in the dataset vs images labelled with “iktsuarpok”.

Another bias is the labelling of data. The generic labelling of data creates a simplified model of what an image contains. This problem can lead to stereotypes (which can create sexist and racial biases), but it can also lead to an even more simplistic language of art. Dataset labelling of existing artworks or images will favour who labels them and lack the art-historical and political context. It will favour common basic knowledge (for example, celebrities) over niche knowledge and language-specific content. There’s also a risk it will have no meta-content, such as alternative descriptions of the content and other related texts. Attempting to increase the complexity of the labelling will most likely increase the global-north bias based on the worldview of the labeller or label software.

Presentation and access

The presentation of “new” AI art follows the modernist/colonial recipe where affluent artists get access to the tools first because of their social privilege, access to education, access to capital (social, financial etc) and location. The artworks made with AI get presented to the less affluent and create a classic cultural hegemony that directs culture and justifies using capital, natural resources and human labour to generate these spectacles (Gramsci and Debord). The supposed criticality from contemporary artists involved in these presentations obfuscates all the biases and material conditions. The presentation of this new spectacle sells the dream of infinite images and a new technical tool that will revolutionize art. This follows the neoliberal capitalist logic of growth, where you constantly need to expand and extract more resources to keep going without accounting for externalities such as natural resources, energy consumption and access. What’s the next big dataset? What if you can do even larger images? What if we could generate CG AI? Revolutionizing art is not done through a tool but by understanding art and its use.

There has not been a lack of tools to create images you can generate with AI through prompts (you could photoshop them together). It has been a lack of imagination and understanding of what art is. This lack of imagination will continue regardless of how advanced tools you get (VR, video, games and “intelligent” AI’s), as long as the global north controls it. The complacency, immediacy and “newness” are what creates the spectacle.

AI art is largely dependent on the latest technology development and access to cheap material resources. By making itself dependent on the spectacle of technological progress, it’s also dependent on large tax-evading multinational corporations such as Meta, Alphabet, Amazon and OpenAI (Microsoft). For affluent artists to maintain the cultural hegemony they are in need to adopt the latest development of AI as soon as it is released (preferably before it’s public).

The material reality of AI

From: Energy consumption of AI poses environmental problems

OpenAI trained its GPT-3 model on 45 terabytes of data. To train the final version of MegatronLM, a language model similar to but smaller than GPT-3, Nvidia ran 512 V100 GPUs over nine days. A single V100 GPU can consume between 250 and 300 watts. If we assume 250 watts, then 512 V100 GPUS consumes 128,000 watts, or 128 kilowatts (kW). Running for nine days means the MegatronLM’s training cost 27,648 kilowatt hours (kWh).

Meanwhile, the largest data centres require more than 100 megawatts of power capacity, which is enough to power some 80,000 US households, according to energy and climate think tank Energy Innovation.

From: Curbing the Growing Power Needs of Machine Learning

It’s also inference (the use of a finished model, such as an NLP model) and not training that draws the greatest amount of power, suggesting that as popular models are commodified and enter the mainstream, power usage could become a bigger issue than it currently is at this more nascent stage of NLP development.

This does not account for the amount of hardware needed to run these models, the rare metals needed in this hardware and the assembly and production of the server. Many of these rare metals are extracted from mines under slave-like conditions in the global south.

According to James Hickel, rich countries drained $152tn from the global South since 1960, imperialism never ended, it just changed form.

This study affirms that drain from the South remains a significant feature of the world economy in the post-colonial era; rich countries continue to rely on imperial forms of appropriation to sustain their high levels of income and consumption.

and

Note that these figures represent resources and labour embodied not only in primary commodities but also in high-technology industrial goods such as iPhones, computer chips, cars, designer clothes, etc., which over the past few decades have come to be overwhelmingly produced in the South.

From: Environmental Justice Atlas:

Glencore-Katanga Mining Ltd., Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)

Environmental Impacts Visible: Groundwater pollution or depletion, air pollution, Biodiversity loss (wildlife, agro-diversity), Soil contamination, Soil erosion, Surface water pollution / Decreasing water (Physico-chemical, biological) quality, Mine tailing spill.

Health Impacts Visible: Violence-related health impacts (homicides, rape, etc..), Occupational disease and accidents

Socio-economical Impacts Visible: Increase in Corruption/Co-optation of different actors, Displacement, Increase in violence and crime, Lack of work security, labour absenteeism, firings, unemployment, Militarization and increased police presence, Violations of human rights

Findings As of 2015, the USA was responsible for 40% of excess global CO2 emissions. The European Union (EU-28) was responsible for 29%. The G8 nations (the USA, EU-28, Russia, Japan, and Canada) were together responsible for 85%. Countries classified by the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change as Annex I nations (ie, most

industrialised countries) were responsible for 90% of excess emissions. The Global North was responsible for 92%. By contrast, most countries in the Global South were within their boundary fair shares, including India and China (although China will overshoot soon).

From: Innocenti Report Card 17: Places and Spaces

The report compares how 39 countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and European Union (EU) fare in providing healthy environments for children. The report features indicators such as exposure to harmful pollutants including toxic air, pesticides, damp and lead; and countries’ contributions to the climate crisis, consumption of resources, and the dumping of e-waste.

“Not only are the majority of rich countries failing to provide healthy environments for children within their borders, but they are also contributing to the destruction of children’s environments in other parts of the world,” said Gunilla Olsson, Director of UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti. “In some cases, we are seeing countries providing relatively healthy environments for children at home while being among the top contributors to pollutants that are destroying children’s environments

abroad.”

From the real amount of energy a data centre use

Knowing how much electricity is used by worldwide data centers, on the other hand, is a good way to assess assertions regarding the impact of data center services on CO2 emissions. A common assertion is that data centers in the world emit as much CO2 as the worldwide aviation sector, which is around 900 billion pounds of CO2. Given that global data centers recently consumed over 205 billion kWh, their average power emissions intensity would have to be roughly 4.4 kg CO2/kWh for this claim to be correct.

The increase in energy and resource consumption to provide the mainstream with access to these AI models is evident. Making this a new standard of what memes, image making etc should be like for a global north citizen will effectively increase the energy spent per user on the internet. Most of this cloud architecture is abstracted away from users so they have no idea about the energy consumption of their daily habits. Neoliberal capitalism outsources and abstracts away the costs of consumer and user habits. With this abstraction, it’s possible to continue resource exploitation and environmental destruction. The increased energy usage of data centres is also connected to fossil fuel consumption and contributes to the destruction of the future for much of the global south.

Positive aspects of AI

Considering the potential of AI and its ramifications, it would be better if we focus on solving our current global issues. While AI is a part of the problem, we could consider it powerful enough to be used for solving our current crises. By restricting the use of AI from the general public (including art) and focusing on use cases that increase global human well-being, we could potentially solve some of the current bottlenecks in our society. Some possible use cases could be: increasing the output per solar panel and lowering the costs of solar power, lowering the cost of geothermal energy, optimising green transportation of goods and supply chains, finding new types of clean renewable energy sources and reinventing sustainable packaging. This could be an acceptable way to use AI despite its downsides. However, this would be very close to a “green growth” perspective which is an ecomodernist fantasy that is hard to achieve due to capitalism’s need for exponential growth.

From: Is Green Growth Possible? By Jason Hickel & Giorgos Kallis

Green growth also requires that we achieve permanent absolute decoupling of carbon emissions from GDP, and at a rate rapid enough to prevent us from exceeding the carbon budget for 1.5°C or 2°C. While absolute decoupling is possible at both national and global scales (and indeed has already been achieved in some regions), and while it is technically possible to decouple in line with the carbon budget for 1.5°C or 2°C, empirical projections show that this is unlikely to be achieved, even under highly optimistic conditions.

Responsibility

Art should be a practice of human flourishing and not increase the suffering of humans and other living beings on earth. While it’s impossible not to cause suffering to other living beings under neoliberal capitalism, we should question the necessity of art to become even more energy-intensive, the need for AI to be a pastime activity (in the form of memes etc) and in general lower our consumption of energy and goods.

From a Buddhist perspective of interbeing, each AI image carries the slave-like conditions that western imperial forces maintain. It also carries the extraction of natural resources for the high-end data centres filled with chips with parts taken from the global south. It also carries with it the continued suffering of humans affected by the conditions it creates.

AI-based artists are responsible for their share of maintaining a global imbalance in their need for new computers/servers produced under these conditions and the increased energy consumption that comes with new technologies. The biased presentation of this technology without mentioning the ramification of its production and planned obsolescence perpetuates the idea of harmless new technology and infinite possibilities. Artists are also responsible for using datasets with many biases disfavouring the global south. All of this can be seen in each AI art piece; you must look carefully.

Leave a Reply