Originally published by Ecocore.

Neo-liberal capitalism seldom accounts for the energy spent in pursuit of useless aesthetics. By useless, I mean items and activities that lead to environmental degradation without providing much social and public value. Capitalism allows your desires to be pursued without a need to justify them. The freedom it provides is built on false premises.

Endless choices offer the freedom to pursue hobbies and pastime activities (after you have worked a job) without concern for environmental and human costs. This is not a freedom that can be sustainable but one that is complicated to change because its costs are obfuscated and not accounted for. Capitalism will continue to make you pursue unrealistic freedoms as it is aligned with neo-liberal ideals and the current political project of the global North.

As Dipesh Chakrabarty puts it in The Climate of History: Four Theses:

In no discussion of freedom in the period since the Enlightenment was there ever any awareness of the geological agency that human beings were acquiring at the same time as and through processes closely linked to their acquisition of freedom. Philosophers of freedom were mainly, and understandably, concerned with how humans would escape the injustice, oppression, inequality, or even uniformity foisted on them by other humans or human-made systems. Geological time and the chronology of human histories remained unrelated. This distance between the two calendars, as we have seen, is what climate scientists now claim has collapsed. The period I have mentioned, from 1750 to now, is also the time when human beings switched from wood and other renewable fuels to large-scale use of fossil fuel—first coal and then oil and gas. The mansion of modern freedoms stands on an ever-expanding base of fossil-fuel use. Most of our freedoms so far have been energy-intensive.

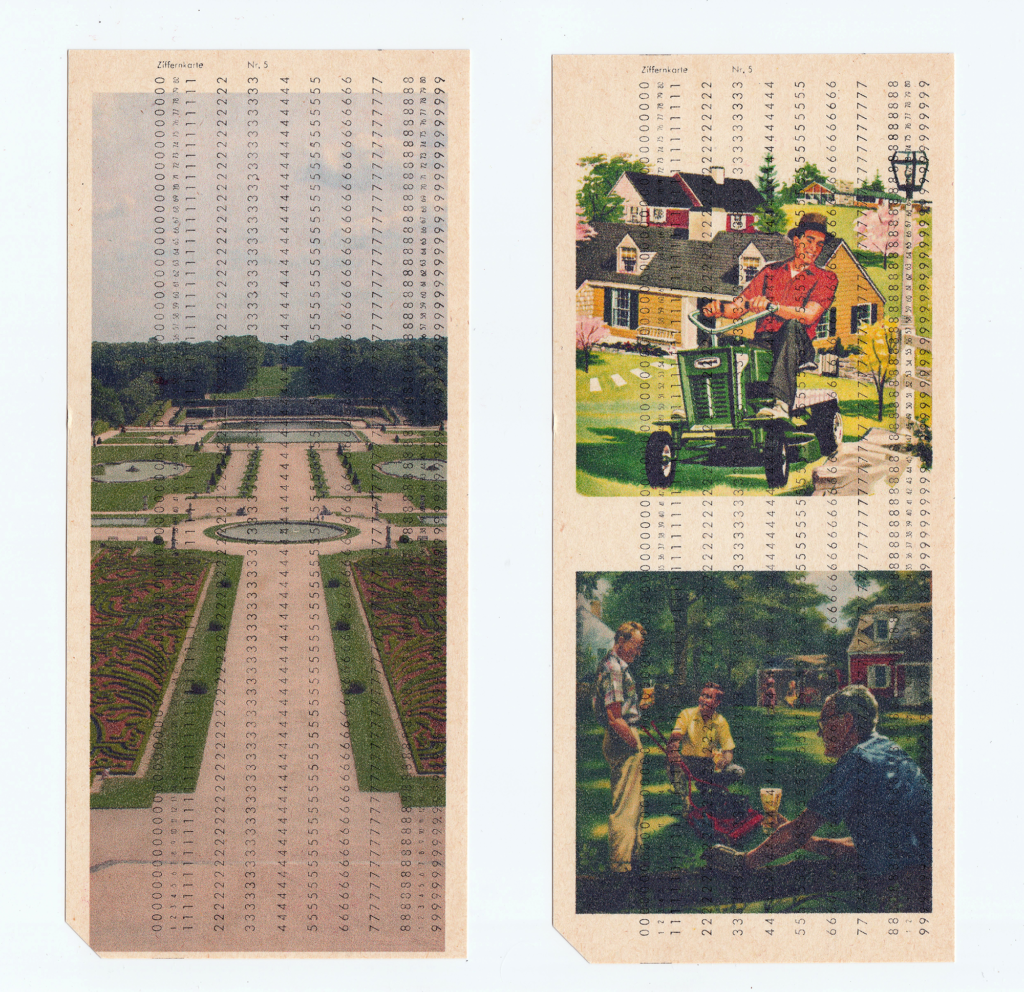

The lawn people

One of the more energy-intensive traditions born out of settler colonialism is the lawn. Grass is the biggest irrigated crop in the US, accounting for up to 30% of a family’s water usage. 64 million litres of gasoline is spent on refuelling lawn equipment, polluting and degrading the soil. Over 40 million acres of land (which equals 1.9% of the surface of the continental United States) have some form of lawn on it. The irrigation of lawns equals three times the amount of irrigation used for all corn in the US. In a dry climate, the water used for irrigation can be up to 50-60 per cent of a household’s water usage. As the world gets warmer, there will be an increased demand for irrigation. While this example focuses mainly on the US, most of this can be applied to the global North.

In Lawn People, Paul Robbins outlines:

Participation in maintenance is a practice of civic good. Disregard for lawn care is, by implication, a form of free-riding, civic neglect, and moral weakness. This is further reinforced by the ecological character of lawn problems, including mobile, invasive, and adaptive species such as grubs, dandelions, and ground ivy. These pests, if eliminated in one yard, can easily be harbored in another, only to return later, crossing property lines, blowing on the wind, and burrowing underground.

Intensive care by one party merely moves problems around; only coordinated action can control “outbreaks” and achieve uniformity. In this sense, lawn care differs from other kinds of individual investment in community, such as Christmas lights, painting, or other efforts. It is a far greater problem, requiring coordinated collective action, at least where green monocultural results are desired. As such, intensive lawn management tends to cluster.

If your neighbor uses lawn chemicals, then you are more likely to engage in intensive lawn care, (e.g., the hiring of a lawn care company or the using of do-it-yourself fertilizers and pesticides). In addition, lawn management in general is associated with positive neighborhood relations. People who spend more hours each week working in the yard report greater enjoyment of lawn work, but also feel more attached to their local community. Yard management is not simply an individual activity but is instead carried out for social purposes: the production and protection of neighborhoods.

A brief history of the lawn

The development of the lawn in the US came from North American settlers that mimicked the manor lawns of the British aristocracy and provided a symbol of wealth and power. It’s also connected to the rise of agriculture, clearing vast amounts of forest for farms, and destroying the ecosystems that existed there. Various indigenous communities maintained the North American landscape before the settlers came and invaded their land and killed or removed indigenous communities.

Crowfoot, chief of the Blackfeet, circa 1885:

Our land is more valuable than your money. It will last forever. It will not even perish by the flames of fire. As long as the sun shines and the waters flow, this land will be here to give life to men and animals. We cannot sell the lives of men and animals; therefore we cannot sell this land. It was put here for us by the Great Spirit and we cannot sell it because it does not belong to us. You can count your money and burn it within the nod of a buffalo’s head, but only the great Spirit can count the grains of sand and the blades of grass of these plains. As a present to you, we will give you anything we have that you can take with you, but the land, never.

Before the electrical mower, the lawn was exclusively for extremely wealthy estates and manor houses of the aristocracy. It was very labour-intensive to maintain a lawn, and you needed several people to keep them intact. With the industrial revolution, people had more leisure time, and suburbia was created. The combination of the electric lawn mower and suburbia made the lawn a popular symbol of success, wealth, and power.

After World War II, the use of pesticides and artificial fertilisers (closely connected to the military-industrial complex) increased. Combined with the new suburbs on the fringes of cities, it opened up for Levittowns, cookie-cutter homes with a pre-installed lawn. Most of what signals wealth and power are often adopted by the middle class and the working class in some cases. What Gramsci called cultural hegemony makes the lawn a symbol that the middle and working class strives to acquire.

From Lawn People by Paul Robbins:

Second, people who practice intensive lawn care do, to some degree, resemble the rigid caricatures in advertising photos promulgated by the chemical industry. As suggested in “pull” marketing, these lawn people are dedicated to family and community and they feel obligations of stewardship to the landscape itself. Clearly advertising does not produce this effect, however, since the source of such behaviors is rooted in the social community and the landscape. Even so, the mutual mimicry of the social-communitarian subject and of the economic consuming subject is relevant to our understanding of the lawn, which serves as a bridge between the two.

Desire and community obligation cannot in themselves be marketed as commodities, after all, as deeply held “feelings” they provide no outlet in and of themselves for economic growth or accumulation. But as embodied in intensive lawn practices, such desires can be bought or sold to provide an industrial source of revenue and a sink for risk. To produce and maintain this link between consuming and participating, the lawn industry projects back to lawn people images of communities that can be actively achieved through hard work and the right commercial products.

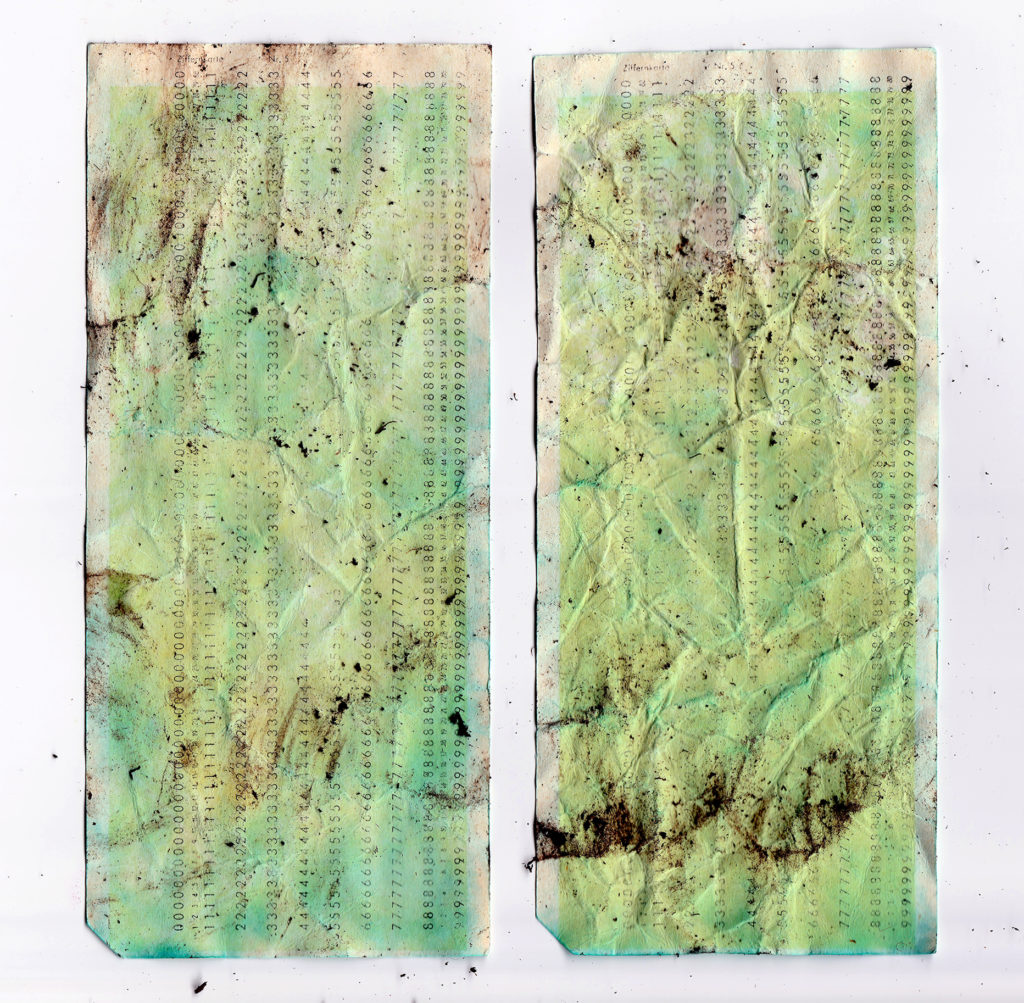

As lawns have become ingrained into western society and traditions, people connect emotions to this destructive tradition. This makes it even harder to dismantle because it symbolises a false sense of security, community and nostalgia.

40 million acres of fruit and nut trees

Shifting the public perception of what a lawn can be used for is a daunting task that we haven’t even started. It will require a mental shift from what is of use value and that many of your desires are fuelled by neo-liberal capitalism and fossil fuels. While most of the 40 million acres of land were taken from indigenous people and turned into farmland, a renegotiation should occur. We should also look at how Native Americans tended their land as how we can tend the 40 million acres of lawns (US alone). Taking a fruit tree as an example, you would need around 15 ft spacing between each tree. This would amount to 70 trees per acre. That would amount to approximately 2.8 billion fruit trees on 40 million acres. You create a polyculture food forest, much like how the land was before the settler colonialists came to North America, which would be ideal. An even better approach is to make a majority of that land publicly owned food forests so everyone in the local community can enjoy and tend the land. Trees are also a significant carbon sink and shade provider, so increasing the number of trees in urban areas would be ideal as we creep towards a warmer climate.

This is just out of many examples of how a capitalist society obfuscates and confuses use-value and needs. A substantial amount of energy, fossil fuels and human labour are used to maintain a destructive colonial tradition while all those resources can be used for food security and building stronger community bonds.

Leave a Reply